|

The JBC Minimumweight title has been in existence since the mid 1980's and has been an interesting title. It's been held by 29 fighters since it's inception, and has been held by a number of world champions. It may not be the most prestigious of titles, but it's certainly an interesting one with a solid list of former champions.

With that in mind we thought it was a great idea to cover the belt in our latest "Did you know..." -Kenji Ono was the first champion but not only fought in the first ever Japanese Minimumweight title fight, beating Missile Kudo for the belt, but less than 3 months later he was also involved in the first ever OPBF Minimumweigjht title bout, losing to Samuth Sithnaruepol. -Missile Kudo, who lost to Kenji Ono in the inaugural bout for the title, would win the belt at the third time of asking but lost in his first defense. Incidentally his career record was 10-12-2 (3), meaning he had more losses than wins -A staggering 4 men held the title in 1988! These were Kenji Yokozawa, who began the year as the champion before vacating early in the year, Yasuo Yogi, who held the title from February 25th to June 27th, Missile Kudo, who held the belt from June 27th to November 13th, and Hisashi Tokushima, who was the last champion of the year. This is even more peculiar when you consider there wasn't a single bout for the title in 1989! -Kusuo Eguchi and Katsuaki Eguchi, who fought for the vacant title in June 1993, were brothers! This is the only time a Japanese title has been fought for by brothers! -The most defenses of the title is a record jointly held by Rocky Lin and Satoshi Kogumazaka, who both defended the title 7 times -Makoto Suzuki is the only fighter to have had multiple reigns, holding the belt twice. His first reign ran from June 1999 to January 2001, when he lost to future world champion Yutaka Niida, whilst his second reign ran from September 2001 to September 2002, when it was ended by previous interim champion Hiroyuki Abe -Hiroyuki Abe's interim title reign is the only time the title has been held as an interim belt, and that only lasted from June to September 2002. -World champions who have held this title are Hiroki Ioka, Keitaro Hoshino, Yutaka Niida, Katsunari Takayama, Akira Yaegashi and Tatsuya Fukuhara -Having just mentioned Katsunari Takayama it's interesting to note that he won a world title, then the Japanese title, then went back to world level, claiming more world titles as he completed his "Grandslam" of world belts.

0 Comments

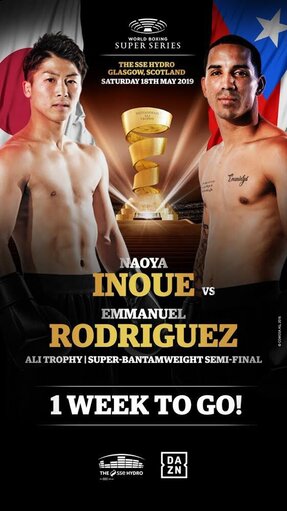

On May 18th we'll see Japanese star Naoya Inoue (17-0, 15) attempt to progress to the WBSS Final, as he takes on Emmanuel Rodriguez (19-0, 12). The bout, for the IBF, WBA "regular" and the Ring Magazine Bantamweight title is really highly anticipated though is strangely regarded as a mismatch with the bookies. At the time of writing the book makers in the UK have Inoue priced at 1/7 to win with Rodriguez priced as high as 25/4. This isn't going to be one of our looks into the odds however, and is instead a bit of a history piece, suggesting that those odds really are remarkable, and that a win for Inoue would actually be an historic milestone for Japanese boxing. In fact it would end a 51 year barren run for Japanese fighters travelling to Europe in world title fights. It would be a first in a number of ways and could be a real turning point in the way Japanese fighters figure in Europe. It's long been accepted that Japanese fighters don't do well on their travels. They have had notoriously bad form in nearby Thailand, as well as the US and Mexico. What is often over looked however is that they are 0-20 in world title fights in Europe. A figure that is incredible given the talent Japan has given us. Worryingly it's not just been lesser challengers who have come up short when they have travelled continent but some really good fighters as well. And their misfortune runs across Europe, from Russia to the UK. So lets roll back the clock. The first loss by a Japanese fighter in a world title fight in Europe came way back in 1968, when Mitsunori Seki fought Howard Winstone for the WBC Featherweight title. Both men had been leading contenders, essentially unable to over-come the legendary Vincente Saldivar, who beat Winstone 3 times and beat Seki twice. When Saldivar retired the two fought for the title he vacated with Winstone stopping Seki in the 9th round, retiring the Japanese fighter. The difference between then and now is huge. Back then there was only 2 titles, the WBC and WBA titles. Despite both fighters being top contenders they were both in their mid 20's, with Seki being the younger man at 26 and Winstone being 28. Despite that Winstone was figthing for the 65th time whilst Seki was in his 73rd bout. We don't often see careers like that any more. Interestingly neither man would fight beyond the year, with Seki retiring after this loss and Winstone retiring following his title loss 6 months later. It would take 6 years before another Japanese fighter travelled over for a shot at glory, with that being Lion Furuyama in 1974. The Japanese fighter had a win some-lose some record but would come close to upsetting Perico Fernandez in a bout for the then vacant WBC Light Welterweight title. The bout took place on neutral soil, in Italy, and was decided by Ronald Dakin's card of 148-147 to Fernandez. Yes the bout was decided by a single round of the scoring referee's card. This is as close as a Japanese fighter has come to clinching a world title in Europe. Interestingly both Furuyama and Fernandez would go on to suffer 2 losses to Thai legend Saensak Muangsurin, with Fernandez being the man Muangsurin beat for the title in his third bout, and Furuyama being the man he beat in his second bout. The third occasion, at least the third one we could find, was 13 years later, taking place in 1987 in the UK and comes from a peculiar time in Japanese boxing history. This bout saw Akio Kameda travel to face Terry Marsh for the IBF Light Welterweight. At the time the JBC didn't recognise the IBF at all, holding that stance until very recently. As a result Japanese fighters who wanted to fight for IBF titles fought under the alternative IBF Japan. A number of fighters did this, including Satoshi Shingaki. Kameda became the first, and only, IBF Japan fighter to travel to the UK to fight for a world title. Marsh broke down Kameda until the Japanese visitor's team stopped the bout between rounds 6 and 7 in what was the final bout for both men. Despite the long break between Furuyama and Kameda getting shots there wasn't a long wait for the next one, with Akinobu Hiranaka travelling to Italy to face Argentinian Juan Martin Coggi for the WBA Light Welterweight title. Although Coggi was an Argentinian the Italian had adopted him following his 1987 title win over Patrizio Oliva, and this was his 4th bout in the country. Hiranaka knew he would need a KO to win and did all he could to get it, dropping Coggi hard in round 3 and having him in all sorts of trouble. Coggi would grit it out though, dropping Hiranaka later in the bout to help secure a wide decision on the cards. Hiranaka would later claim the title, ripping it from Edwin Rosario in 1992, in just 92 seconds. Bizarrely there wasn't a single Japanese title challenger travelling to Europe in the 1990's, from what we found, but since 2004 there has been 16, more than 1 a year. They've all come up short, but they have had mixed performances with some certainly putting up better effort than others. In 2004 we saw both Nobuaki Naka and Yoshinori Nishizawa come up short in firsts. Naka was the first to fight in Denmark, losing in a WBA Super Bantamweight title fight to Johnny Bredahl via a wide decision. Just 9 months after Naka's loss Nishizawa travelled to Germany to challenge WBA Super Middleweight champion Markus Beyer, becoming the first Japanese fighter to challenger for a Super Middleweight title and the first to challenge in Germany. Surprisingly Nishizawa, then aged 38, dropped Beyer before losing a wide decision to the German. The following year Shigeru Nakazato travelled to France, marking the first time a Japanese fighter had challenged in the country, where he was stopped in 6 rounds by the exciting Mahyar Monshipour. Interestingly this card did feature a notable win for Japan, as Toshiaki Nishioka picked up a win against Mustapha Abahraouhi, which was the only win we stumbled on in a none-title fight during our research. It was a return to France in 2006 when Takefumi Sakata battled Robert Vasquez for the WBA "interim" Flyweight title. This was the lowest we found and was another where the Japanese fighter gave a great account, losing a split decision to Vasquez in the first meeting between the two. Despite the loss Sakata would get a shot at the regular title just 3 months later, beating Lorenzo Parra in a third bout between the two men. In his first defense Sakata avenged his loss to Vasquez, winning a decision in Tokyo over the Panamanian. Although there was a rise in activity of Japanese challengers in Europe there wasn't one in 2007. Instead we had to wait until 2008 when Norio Kimura challenged Andriy Kotelnik in Ukraine for the WBA Light Welterweight title. Kimura had come into the bout with a lot of momentum, but was no match for the skills and craft of Kotelnik, who took a wide and clear win over Kimura to make his first defense. In 2009 we were back in Europe twice. The first of those bouts saw hard hitting Middleweight Koji Sato take on WBA Middleweight king Felix Sturm. The dangerous Sato was nullified by Sturms excellent jab and stopped in round 7, suffering the first loss of his career. Sato, who recently revealed that he wanted to competed in the 2020 Olympics, would suffer only 1 other defeat, losing to Makoto Fuchigami in 2011 and we'll speak about him a little bit later. The second bout was another in Ukraine as Motoki Sasaki challenged the then WBA Welterweight champion Vyacheslav Senchenko. Sasaki's technical limitations were a massive obsctable here against the technically sound, though rather uninspiring, Senchenko. The Ukrainian was cut but a clear winner, with Sasaki being deducted points for a headclash in round 6. After a few years where Japanese fighters stayed at home there was a pair of bouts in 2012, and strangely both were at Middleweight and took place within a matter of days. The first of those was in Russia, where Nobuhiro Ishida challenged Dmitry Pirog for the WBO Middleweight title. Despite putting up a solid effort Ishida would lose a wide decision to the excellent Russian, in what would turn out to be his last fight before injury forced him out of the ring. Just days later Makoto Fuchigami, who ended the career of Koji Sato, would face Gennady Golovkin in Ukraine. Sadly for Fuchigami he was totally out of his depth and was stopped in 3 rounds by the Kazakh great, who retained his WBA title. An aside, is that Pirog and Golovkin were meant to meet in the US after this bout, but plans were scuppered by Pirog's injury, meaning Golovkin made his US debut against Grzegorz Proksa, and the rest, as they say, is history. Ishida marked an historic first in 2013 when he challenged Golovkin himself, and like Fuchigami he was stopped in 3 rounds. This bout, in Monaco, saw Ishida become the first Japanese fighter to challenge for a world title in Europe twice, and the first to lose twice. He would however remain a popular figure and twice fight for the Japanese Heavyweight title afterwards. The bout between Ishida and Golovkin wasn't the only time a Japanese fighter world travel in 2013. The other saw Yuzo Kiyota challenge Robert Stieglitz for the WBO Super Middleweight title, Kiyota was a deducted a point early against the German champion and later stopped on cuts. Originally the result was announced as a technical decision win for Stieglitz, himself a very poor champion, though was later reviewed and changed to a TKO win. At the time of writing Boxrec incorrectly lists, in the wikipedia for the fight, that this was the first time a Japanese fighter had challenged for a world title at 168lbs or higher. That was, however, Yoshinori Nishizawa back in 2004 who did it twice, first against Anthony Mundine in Australia then again against Markus Beyer in Germany. In recent years the UK has seen Japanese challengers coming over on a pretty regular basis, about 1 a year. The first of those was in 2014 when Hidenori Otake travelled to challenger Scott Quigg, the then WBA Super Bantamweight champion. Otake put up a brave effort, and showed incredible toughness, but struggled to have any great success against the much sharper Quigg. The following year Ryosuke Iwasa travelled to face Lee Haskins for the vacant IBF Bantamweight title. This was regarded as a 50-50 match up, though unfortunately Iwasa was stopped in round 5, following a peach a shot from Haskins. Iwasa, like Hiranaka, would later go on to win a world title, moving up in weight to take the IBF Super Bantamweight title. In 2016 Keita Obara travelled to Russia to challenge the then IBF Light Welterweight champion Eduard Troyanovsky. Obara had moments in this bout, and seemed to wobble Troyanovsky at one point, but was knocked out of the ring in round 2 before later being stopped the same round. At the time of writing this is the last time a Japanese fighter challenged in Europe, but not in the UK. We saw two Japanese fighters travel to the UK challenge for world titles in 2017, both challenging WBA Super Flyweight champion Kal Yafai. The first of those was Suguru Muranaka, who proved to be incredibly tough and gutsy, but lost a clear decision to Yafai in Birmingham. Following Muranaka was the more skilled Sho Ishida, who asked questions of Yafai but fought far too tamely to take the decision. Despite the wins over the Japanese pairing Yafai did little to enhance his reputation with the wins and has failed to shine since. With a 20 fight losing streak in world title bouts in Europe Japanese supporters may need to be a little cautious of Inoue ahead of the fight with Rodriguez. It's not a gimme for Inoue, as the betting suggests, and although he's, easily, the best Japanese fighter to have fought in Europe he is going to be well aware that history is not on his side. Over the last few weeks we've seen DAZN snapping up talent and building a very strong stable of fighters to work with through different promotional tie ups, notably working hand in hand with Matchroom US, World of Boxing and Golden Boy Promotions. They have seen the streaming service become more talked about than almost any fighter in the sport right now. One market they've not yet cracked, at least for boxing, is the Japanese market, despite being available in the country for quite a while now. DAZN is available in Japan, and is relatively big there with rights for things like the NPB (Nippon Professional Baseball), UEFA Champions League, La Liga, Premier League, the J League, F1, various Tennis and Rugby competitions, a number of MMA companies and even some professional darts. Their content library is solid in several areas, but not in boxing. They do also show some boxing, but by some I really do mean "some". Most of their boxing content is from the US, and whilst that has shown some Japanese fighters, including Ryota Murata, Ryohei Takahashi and Takeshi Inoue, they haven't exactly been shown at prime time. Instead they have been shown live, at the same time as their bouts have taken place in the US, giving them a mid-day type of time slot. The idea seems to be for the channel to appeal to Japanese audiences on the value of Western fighters, which does have it's place with Japanese fight fans, though maybe not as big of a place as DAZN would like. This means that not only are the fans rarely able to see Japanese fighters on the service, but that a lot of the fights they get on the service aren't at a great time for their audience numbers, and there is actually a pretty good reason for this. The rather unique thing about Japanese boxing is that, for the most part, their biggest fighters are available on free TV. Fighters like WBA "regular" Bantamweight champion Naoya Inoue, WBO Super Featherweight champion Masayuki Ito, WBC Light Flyweight champion Kenshiro, WBC "interim" Bantamweight champion Takuma Inoue and former WBA "regular" Middleweight champion Ryota Murata are all linked to Fuji TV, for fights held in Japan. On the other hand WBA "super" Light Flyweight champion Hiroto Kyoguchi, former 3-weight champion Kazuto Ioka, former unified Light Flyweight champion Ryoichi Taguchi are all inked to TBS, and WBO Flyweight champion Kosei Tanaka is inked with TBS' affiliate CBC, which allows TBS to show his fights. Notably it does look like it's not just the present tied up with TBS and Fuji TV but also the future with TBS having a working relationship with Watanabe, who promote prospects like Ginjiro Shigeoka and Seiya Tsutsumi as well as up coming world title challenger Masataka Taniguchi, whilst Fuji's deal with Ohashi Gym is likely to see Fuji having exclusivity on Satoshi Shimizu and Taku Kuwahara, among others. The only real outlier to this is Tomoki Kameda, who does have a streaming deal, albeit with Abema TV, who have shown his last few fights for free. They appear to be working strongly with Kyoei and the Koki Kameda TFC series of shows, so Kameda is also off the table, at least for now. Unlike in the US Japanese fight fans aren't accustomed to paying for boxing, especially not for their top guys. They also see their fighters fighting on free TV in front of a multi-million people audiences, with their profiles becoming huge as a result Saying that however they have had the ability to pay for some boxing, with Boxingraise offering some VOD and live domestic action, G+ being a premium service that shows a monthly live domestic card and WOWOW showing some international content, but on the whole it's rare to see boxing on pay TV in Japan. Even services that did once offer paid options, such as GAORA and Sky A+ have now all but stopped their boxing content. GAORA hasn't shown anything in years and we believe the last Sky A+ boxing card featured Naoko Fujioka against Shindo Go. If we do look at the available pay options for Japanese fans they cater to 2 different markets. Boxingraise is outlier in a lot to how boxing content works in Japan, with it being a combination of a streaming and Video on Demand service. It is run by Dangan, who promote a number of shows every month, and is available online. It is a boxing only service, that typically shows 1 live card a month and adds 4 or 5 new shows on a delay basis, whether it's a classic card or a recent one is dependent on the activity of any given month. At ¥980 it's affordable, but it is boxing only content, and will cater to those who are hardcore fans only. Notable this is actually available outside of Japan though is one that only hardcore fans are ever likely to be interested in. WOWOW is a general premium service, showing a combination of movies, live content, musical concerts and things like the Oscars. Basically if you get WOWOW you're unlikely to get it mainly for the sport. It has a traditional fan base, having been around since the 1990's and it's boxing content is not significant enough to get the channel just for boxing. Think of it as the Japanese Showtime, without PPV if you will, with plenty of wide ranging contest. In regards to boxing it only shows big US bouts, often on delay. Some fighters are live but usually it's a delay broadcast. G+ is a more clear premium sports channel, and is a channel that is linked with free TV giant NTV. This is more of your Sky Sports type of thing, showing sport through the day with things like classic wrestling, golf, NASCAR, Boxing, a combination of classic, live and magazine shows. On average they do 1 live boxing card a month, though there is some leeway with that, and it's on a Saturday afternoon/evening, as part of their long established Dynamic Glove series. To add the channel on to a typical satellite package is ¥900, though of course you will need a satellite package to begin with. When DAZN launched in Japan it's main rival likely was SKY A+ and G+, both of which are premium sports channels. As mentioned SKY A+ no longer seems to show boxing, or haven't done for a while, but as a general sports channel it is DAZN's rival.

When DAZN launched in Japan it did so at a price point of ¥1750. Yet for a boxing fan, who already has a CS Satelite set up, that's not significantly cheaper than paying for G+ and Boxingraise, and getting a couple of live domestic cards, some archive stuff and getting the other benefits that come with G+. The pricing for SKY A+ is a bit more complicated than for DAZN or G+, due to it's tiers, but on the whole it does cost more than DAZN. It offers multiple channels, through the TV with multiple services on some of it's packages. With it not showing boxing however it's difficult to really talk about them as competition here, as in for this particular market, but they are certainly rivals in terms of general sports content. What DAZN is likely to do is to make SKY A+ cut their pricing and perhaps even force them to offer more versatility to their services, just to compete with what DAZN are offering. However that seems like it will just benefit consumers more than anything, at least in the short term. The big issue that DAZN is facing when breaking into the Japanese market, for boxing, is that it lacks live content in prime time. We suspect that we'll see Matchroom and Goldenboy using more Japanese challengers, to try help their broadcast partner's Japanese arm. What DAZN needs to make it in Japanese boxing market is a deal with a domestic promoter, at least one. Unfortunately for them it's hard to see where they go in regards to inking with a top promoter but there are options out there. A starting point could be World of Sport Boxing, who promote Takeshi Inoue, Japanese Middleweight champion Kazuto Takesako and a couple of promising prospects. Along with Shinsei Gym, who promote Etsuko Tada, Reiya Konishi, Shun Kubo and Yuki Yamauchi, though they have had a working relationship with Fuji TV in recent times. As well as the likes of Yokohama Hikari and Ichi Riki, who have worked together a lot recently. Between them they have not only Ryohei Takahashi but also Akihiro Kondo, Ryo Akaho and Keita Kurihara. It's also worth noting that Naoko Fujioka has worked on the same shows as the Ichi Riki and Yokohama Hikari fighters in recent times, which would give them a chance to continue that relationship If DAZN could link with those promoters they wouldn't have male world champions, but they would have 2 female world champions, a regular and steady stream of live shows in and around prime time, with the potential to build the names of fighters who could fight for world titles. For example Inoue is likely to get another shot down the line, Konishi is set to get a second world title fight, Kubo is world ranked and a former world champion, Kondo is set for a world title eliminator, and the prospects that they would tie up would give them a longer term plan. It would also allow DAZN's international arms a chance to showcase Japanese fighters before they get big fights, meaning that the likes of Takahashi and Inoue would have been more well known before making their US debuts recently. Will DAZN link up with Japanese promoters? There hasn't been much rumour about it, but we wouldn't be surprised if it happens in the future. It does make sense from a boxing point of view, and would be beneficial to the fighters, the promoters and DAZN as a whole, not just the Japanese arm, allowing them more content for their various international services, and help entice Japanese fight fans to buy into the service.  Boxing is one of the most international of sports. Whether you fight in Tokyo or Texas the sport is the same with two fighters and a referee in a ring with the fighters trying to win the majority of the rounds or score a knockout to win. At it's core it's a very simple sport to understand. Sadly whilst it's simple to follow in the ring the out of the ring part of the sport seems to be a mess all too often with little being done to stop mismatches and next to nothing being done to stop fighters padding out their records for years. At the moment there are fighters around various parts of the globe with records that fail to suggest how talented, or limited, they are. For example after 31 fights we have no idea how good Deontay Wilder is, or after 17 fights how good Chris Eubank Jr is. Lets be honest when a fighter in Japan gets to 17 fights we tend to have some sort of an idea as to how good, or bad, he is. So what exactly can the west learn from Japan to stop massive record padding, mismatches and and even improve the quality of it's fights and fighters.  Licensing Every fighter who turns professional in Japan needs to earn a license. This done with a 2-part test. Part of that test is a written test to prove they know the rules and understand the sport, like any fighter should. The other part is a practical test where a fighter takes part in a public sparring bout with headgear on. This is to prove that they can box and they can take the skills into the ring. It might seem like a lot to get a license but it also allows the Japanese Boxing Commission (JBC) to "grade" fighters. A normal guy who wants to take up the sport would, if they past the tests, usually earn a C grade ranking, that of a novice with out much in terms of an amateur background. A C grade license allows a fighter to fight in 4 round bouts against other C grade fighters. This keeps the fighters on a similar level to each other so we can't have mismatches between two domestic fighters. If a fighter if a former stand out amateur they will usually go for a B grade license before they turn professional. This means that they have to spar, and at least hold their own, with a decent fighter in their public test and they usually have to have proven their ability. Recent fighters who have began their careers with B licenses have included Naoya Inoue and Ryota Murata both of whom were exceptional amateurs. A B license not only allows you to fight against other B license fighters but also permits you to fight in 6 round bouts After you've proven yourself you can obviously move up through the license system to claim an A license and be eligible for title fights and any bouts of the 8 round distance. If you're good enough you can progress very quickly, as we've seen from Kosei Tanaka for example who looks set to fight for a title in his 4th professional contest.  Stepping Stones to a World Title Not only do the JBC enforce their licensing to get fighters to prove their ability but they also have a domestic rule where by a Japanese licensed fighter cannot fight, in Japan, for a world title before winning either the Japanese title or the Oriental (OPBF) title. This perhaps an odd rule in the eyes of some but it does make sense. If you can't prove your the best in the country or the regional area why do you think you're the best in the world? There are ways around this however and if you're willing to fight for a world title outside of the jurisdiction of the JBC you are welcome to fight for a world title. We've seen Tomoki Kameda do this, winning his WBO title in the Philippines, and Atsushi Kakutani did it when he came up short in Mexico against Adrian Hernandez. It seems that for the JBC the idea to step up through the levels and this also legitimises the OPBF and Japanese titles which, in recent years, have had almost every Japanese world champion holding one, if not both, of them.  Banning Poor Imports As well as ruling on domestic fighters they also have rules about imported fighters fighting on shows that they sanction. Unlike almost any other country they want to have a high level of competition and if an important gives a "lethargic effort" they are banned from fighting in the country. It might seem harsh at times but it's something that certainly helps make visitors give their all. As a result Japanese fans get international journeymen like Marjohn Yap who come to win as opposed to just making up the numbers. It's actually in the visitors best interest to give a good effort rather than turn up for the pay day, after all if they get invited back due to being a good test they get paid solidly again. With many journeyman coming from places like Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand the purses they get for fighting in Japan are very handsome when compared to what they would get fighting a domestic level contest. Unlike Britain and the US a journeyman winning in Japan doesn't suggest the journeyman did their job wrong, in fact it means the man they beat usually isn't as good as they think and the journeyman can act as a measuring stick. This way to minimise mismatches would see fewer fighters coming just to lose, especially in the UK where the purse for a journeyman fighting in the UK dwarfs what a fighter would get in Latvia or Hungary for example. As well as the "lethargic effort" ban the JBC do also ban for failing to meet a contracted weight, a lack of skills and in some very rare cases things like "full body tattoo", "name spoofing" and being "immature". It's also worth noting that it's not just journeymen who have been banned but also so pretty big names like Sonny Boy Jaro, pictured, and Liborio Solis, who were both given a year long ban for coming in over-weight. For those interested a full list of banned fighters can be found here, in English.  Free TV Fights being on free to air TV isn't a rule of the JBC but it has helped keeping boxing a relevant sport in Japan. It helped fighters like Shinsuke Yamanaka and Koki Kameda become household names and it has helped the sport remain in the spot light. Interestingly it has also been a success with the likes of TBS, Tokyo TV, NTV and Fuji TV all showing free-to-air boxing. Not only that but they also have some lesser cards on pay TV to help televise more fighters and help those fighters develop an audience before going on to free TV. In many ways this is the opposite of how it works in the US. In the US a fighter often transitions from subscription TV, for example ESPN, to PPV and in the end their audience shrinks whilst their purses grow. It helps the fighters bank account in the US and that's obviously their aim in the sport but it takes away from the people and helps to really minimise the audience. In Japan Sky A Sports often get the rights to lesser bouts whilst Fuji TV's paid sister channels show regular fights as part of their "Diamond Glove" series which often feature OPBF or Japanese title fights. When it comes to world title fights the fighters generally progress from the pay TV circuit to the free TV market. Notably their have been exceptions to this trend but it's a general trend.  Desire to get to the Top In Japan if a prospect is touted highly they tend to want to live up to that hype quickly. Ryota Murata for example is expected to fight for a world title within 15 fights, and fought an OPBF champion on debut, Naoya Inoue won a world title in his 6th fight and Kosei Tanaka called out the Asian champion after his third fight. In the west so many fighters are happy to pad their record whilst developing slowly, or even stagnating, due to a poor level of competition. Going back to Chris Eubank Jr, for example, his 17th fight came against someone who had been stopped by one of his previous victims. The bout made little sense other than to get Eubank a quick victory when he would have been served much better to have fought a British fighter such as Adam Etches, Nick Blackwell, John Ryder or Danny Butler. Of course if Eubank Jr fought one of those 4 aforementioned domestic rivals his risk of losing would have been higher but his development, win or lose, would have been much more important and, if he won, he'd have proven himself ready to challenge for the national title. Instead by beating a very poor important he proved nothing. Public Rankings

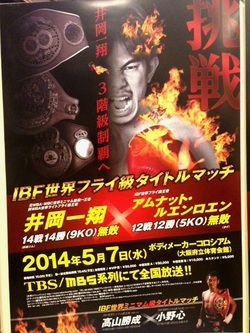

In Japan and in the Philippines the commissions publish domestic rankings every month. This allows fighters to see how close they are to earning a national title fight and also helps them see who is above them. For fans however things are even more telling as we can see what level of competition fighters are really fighting at. For example if the #10 and #9 fight each other then the winner is surely deserving of consideration of the next opportunity in their weight. By Publishing rankings the JBC and GAB show real transparency and we, as fans, can follow the moves month after month. We can criticise the changes that don't make sense, we can see who is deserving of a title fight and we can see who doesn't belong in a title fight. It seems very odd that the BBBofC don't publish these and adds to the feeling that British Board are secretive. It's a shame that the sport isn't more transparent but of course the more transparent it is the more the boards, commissions and authorities leave themselves open for criticism, something they tend not to like. As well as the 6 issues outlined above there are numerous others that some other countries should perhaps take note of, such as the importance of a "home" for boxing like the Korakuen Hall, or even the Gym system. Though they would both take a lot of change to be implemented, and we'd never expect such a drastic set of changes to be made, they really would help the sport in some countries, especially those were promotional cold wars are threatening the sport. (Images thanks to Boxrec.com, TBS and Boxingnews.jp)  As boxing fans we are always talking about the matches we want to see. Whether the bouts are possible or not there are 100's of match ups that we'd like to see ranging from international super fights such as Adonis Stevenson Vs Sergey Kovalev or Floyd Mayweather Vs Manny Pacquiao to fights that we want for selfish purposes such as Kosei Tanaka Vs Takuma Inoue or Ryo Matsumoto Vs Sho Ishida. One bout emerged this past weekend and became a real talking point in both the Japanese press and the online community, including the English speaking boxing forums. Naoya Inoue against Kazuto Ioka. We know some fans in Japan have mentioned this bout for a while and fans in the west have also thought about it, but since this past Sunday the bout seems to have almost become the "Super Fight of Japan" and it's already become more spoken about than a Takashi Uchiyama Vs Takashi Miura rematch or a Shinsuke Yamanaka Vs Tomoki Kameda bout. It has become the most wanted fight in Asian boxing. Interestingly we've spend the past few days thinking about the contest, staying quiet and just thinking about it. Like everyone else we're insanely excited about the prospect of the bout though for now we think the talk is premature. It's a bout that has us licking our lips but we're not likely to get it for at least a year, if not two.  The reasons for why we'd have to wait are numerous but lets look at the key ones. Firstly TV. Inoue is signed to Fuji TV who have helped him become a sensation. The broadcast of his fight with Adrian Hernandez this past weekend got a high of 10% TV share and with the work they've put into help him become a star it's unlikely they'll be in a rush to let him go. We're unsure on how many fights he's got left with Fuji TV but we'd imagine they are more than happy in their working relationship. With only Inoue and Ryota Murata currently signed to deals with Fuji TV we can't imagine the channel handing over any rights to televise Inoue's fights. On the other hand Ioka is signed with TBS who have been broadcasting most of his career so far and are likely to show however many fights Ioka wants as long as the multi-weight world champion continues to remain a big TV draw and an unbeaten fighter. For TBS Ioka is their only current star. They do televise Kameda fights and will show the next Takayama fight, though with the Kameda's not being able to fight in Japan the channel's live coverage is certainly limited right now and they'd refuse to let Ioka go just as Fuji would refuse to let Inoue go.  Secondly we have the issue of weight. We all know that Ioka has moved to Flyweight for his next bout, a challenge for the IBF title against Thailand's Amnat Ruenroeng. The strong reports are that Ioka will then immediately vacate to move up to Super Flyweight. The idea seems to be that Ioka wants to become the first Japanese fighter to become a 4 weight world champion. If he can't become the first he'll instead "just" become the fastest. Of course Ioka's plans depend a lot on Koki Kameda and what Kameda does next. If Koki, as expected, can get a fight with Kohei Kono for the WBA Super Flyweight title we'd expect Ioka to do all he can to get the winner. Koki, by then, could have become the first 4-weight world champion in Japanese history but Ioka will still look towards become the fastest whether he needs to beat Koki or Kono. For Inoue the rumours are that he'll also be at Super Flyweight by the end of the year. For some that's a sign that they'll be negotiating for a Super Flyweight title fight by the start of 2015 though the reality is that Inoue is unlikely to stay at 115 for long if he's already taking a lot out of his body to make 108. The likely outcome is that Inoue ends up at 118 in the next 2 to 3 years as he himself attempts to win more world titles, almost chasing Ioka's records as they get created. It's an interesting question of which weight the bout would be at, though it does appear to make sense that it will be at 115 or 118 with Ioka stating in the past that he wants to be a 5 weight world champion, Bantamweight would be the probable 5th division.  Timing If we take what we know about both men and their current plans and expected plans there could be a serious issue of timing. We know Ioka is fighting in May and we expect him to fight on New Years Eve. We also expect him to move to 115 either in the summer or the winter. For Inoue the plans seem to be rest and then move to 115 by December. Their is no plans, from what we are aware, for Inoue to attempt to grab a slice a slice of the Flyweight crown, though if Ioka does vacate we could see Inoue's plans changing and he could well make a quick stop at Flyweight to pick up a second divisional title. If Ioka dumps off the Flyweight title as expected and moves on to 115 his first fight there would need to be a big one. Fights with Koki and Kono are of course the obvious options though possibilities do lie in Omar Andres Narvaez, or a fight for the IBF title against the winner Zolani Tete/Suguru Muranaka. If Ioka doesn't dump the Flyweight title then those options are open for Inoue if he feels ready for them. Those options would be hugely appealing for both fighters and likely make a lot of sense for them to becoming champions at another weight. We're not trying to be offensive to Tete, Narvaez, Koki, Kono or Muranaka but we'd imagine either Inoue or Ioka would beat them, especially if Inoue and Ioka got another fight of experience at 115 before fighting one of the championship fighters. What we're effectively saying is that they won't meet whilst there other options out there and unless one of them holds a title at 115 the fight wouldn't make a great deal of sense. Why fight a non-title fight when you could face your nemesis for the gold? Better yet, why fight in just a title fight when you could fight in a unification contest? The timing does need to be considered.  Finally the promoters Unlike in the US and the UK promoters in Japan have to work together. The "Cold War" between Top Rank and Golden Boy or the refusal between Matchroom and Frank Warren to really work together isn't possible in Japan. That means promotionally this bout would be easier to make than, for example, Pacquiao Vs Mayweather. Two the promoters involved here would by Hiroki Ioka of Ioka Gym, the promotional outfit that promoters Kazuto Ioka, and Hideyuki Ohashi, the chairman of Ohashi gym. Interestingly the two promoters have had a long rivalry which almost saw them fighting each other back in the 1990's in what would have been a fight similar to this, a huge domestic fight that would have been something special at the time. The last time the promoters worked together on a big fight, similar to this, was back in June 2010 was Ioka promoted the Minimumweight unification bout between Kazuto Ioka and Akira Yaegashi. That bout was brilliant though some, including ourselves, felt Ioka got the decision because he was still unbeaten and because he was the promoters fighter, in fact he was the promoters nephew. Would Ohashi be willing to send his newest star into an Ioka promoted show? Would Kazuto Ioka be willing to fight on an Ohashi show? Would the fight only happen with a neutral promoter, say Teiken or Top Rank? It may seem silly due to the way Japanese promoters have to work together but yet we could still have the promoters making life difficult as they protect their interests. When it comes to the actual fighters we don't imagine either man has a problem fighting the other. We think that, Roman Gonzalez aside, they'd happily fight anyone between 108lbs and 115lbs and aside from the odd exception we'd think they'd be favourites against most in those weight classes, perhaps only Juan Francisco Estrada and Srisaket Sor Rungvisai would be too much at the moment. They'd not mind fighting each other but at the moment it's a case of neither being in the position where the other is the obvious opponent. It's a bout we all want but not one we're expecting in the next 12-18 months. (Images: Top-Inoue courtesy of Ohashi Gym Second from Top-Fuji TV Logo, courtesy of Fuji TV Middle-Ioka v Ruenroeng poster, courtesy of Ioka Gym Second from Bottom-Kohei Kono, courtesy of Watanabe Gym Bottom-Ioka v Yaegashi poster, courtesy of Ioka Gym)  It's widely accepted that Japan is the 10th most populated country on the planet. It's got around 128,000,000 people living on it and this places it between Russia with around 144,000,000 and Mexico 118,000,000. In terms of comparing it with some other boxing countries, the US is the 3rd most populated country with around 317,000,000, the Philippines is the 11th most populated with 99,000,000, Germany is the 16th most populated with around 81,000,000, the UK is the 22nd most populated with around 64,000,000 and Argentina is 32nd with 40,000,000. This means that Japan has less than half as many people as the US, marginally more than Mexico, 50% more than Germany, twice as many as the UK and thrice as many as Argentina. Despite the population being what it is, there seems to be so many more top youngsters coming from Japan than anywhere else. The big question then, is how come so many Japanese youngsters look so talented, so young? At the moment Japan has a wealth of young talent under the age of 25. This includes world champions such as Tomoki Kameda, 22 and Kazuto Ioka, 24, OPBF champions Ryosuke Iwasa, 24 and Masayoshi Nakatani, also 24, up coming world title challenger Naoya Inoue, 20 and more outstanding prospects than I can possibly list such as Kosei Tanaka, 18, Takuma Inoue, 18, Sho Ishida, 22 and Ryo Matsumoto, 20. Maybe, as we've said in the past, Japanese boxing is on the verge of a Golden Age of young talent, a once in a life time boom of youngsters who are all breaking through at the same time. Something tells me this isn't really the case though as 6 is years is a notably long time between the oldest of these guys and the youngest. Personally I think the the real answer lies in the amateur boxing system of Japan and the match making of Japanese fighters .  It may be a surprising to mentioned the amateur scene considering that Japanese amateur boxers haven't been a key fixture at world meets. We rarely see Japanese fighters taking home medals from either the World Amateur Championships or the Olympics, however what we do tend to see is that the top Japanese amateurs don't tend to remain amateur for much longer than they need to. There are, of course, counter examples such as Satoshi Shimizu who has announced plans to compete at the 2016 Olympics, though these are rare. What we have instead are youngsters who have come through the Japanese amateur ranks by fighting regularly in high school and then turning professional at a young age before bad habits and amateur traits are engrained in their style. As well as turning professional at a young age these youngsters also seem to have adapted more professional styles than fighters from around the world. In many countries top amateurs take a number of bouts to learn to adapt. They are basically retrained in how to walk again against a much lower calibre of opponent than they were beating in the amateurs. In Japan however their styles are often fairly professional and they aren't taking huge steps back in their early professional outings. What is the point in going from fighting the elite, either domestically or on the world stage, as an amateur to then fighting domestic level journeymen as a professional? Are we really suggesting that top amateurs, such as Luke Campbell in the UK or Rau'shee Warren in the US need to learn by taking 10 steps backwards? If we look, for example, at Ryo Matsumoto. He did start like a typical "western" prospect fighting a string of weak opponents though by fight #5 he was facing a decent opponent in the form of John Bajawa and in fight #10 Matsumoto will be fighting a multi-time title challenger. As for Luke Campbell's 5th fight he's fighting Scott Moises, a guy who holds an 8-8-1 record. Still Campbell did do better than Warren who faced Jiovany Fuentes, a blown up Flyweight who had been inactive for 2 years. Warren, who now sports a record of 10-0, fought his 10th professional contest earlier this year and faced the very experienced German Meraz who at the time sported a decent looking 46-28-1 record. Unfortunately Meraz hadn't beaten a fighter with a winning record since late 2009 and had only beaten a handful in total. Meraz was the proverbial can crusher with a boosted record that allowed other fighters to look impressive though in reality served as little more than a record padder himself. So as well as having more professional styles the Japanese youngsters are also matched better. They are matched progressively on the whole and take steps up. There is no point in wasting time in this sport as one good shot could finish your career and if you're good enough you're good enough.  Possibly the biggest reason for the boom in Japanese youngsters however is that promoters are willing to take a risk or two. They aren't hiding their talented youngsters in the shallow end of a swimming pool with water wings but are willing to let them swim with sharks. If they get bitten early then it's a rebuilding process and they can cycle things down a gear, as seen in the career of Keita Obara who lost on debut though is now fighting for an OPBF title just a few years later. If a youngster doesn't get bitten however then let them swim with more sharks. Kazuto Ioka is probably the best example right now. In fight #6 he faced an experienced domestic level campaigner, then in fight #7 he faced a highly experienced and unbeaten world champion then in fight #10 he faced a fellow world champion in a world title unification. These were risky fights but Ioka believed in himself, his team believed in him and he showed his worth. In so many places keeping a fighters unbeaten record is actually more important than developing their skills and legacy. You develop by fighting better fighters, you develop by fighting in competitive matches and you develop by needing to prove yourself. Taking a loss along the way is just part of a fighters development. In the US fans are already starting to turn on Gary Russell Jr who has had 24 fights but no risks, Deontay Wilder is similar though has 33 wins with no risk and Sean Monaghan is 20-0 though has again had no risks. Between them these three fighters have had 77 fights yet we have no idea how good they are. Between Ioka, Tomoki, and Naoya Inoue there is a combined 48 fights and already there 2 world champions and a future title contender. US promoters might want to protect their investment and that makes sense, but do you really think Japanese promoters aren't doing the same? The difference is Japanese promoters don't tell you they have a wonder talent then protect him, instead they tell you they have a super talent and they prove it. They don't use smoke and mirrors to sell us a prospect they let the prospect talk with their actions. So why does Japan have so many good, talented youngsters? Well their amateur system seems to promote a more professional style to boxing at a young age, they don't waste time staying in the unpaid ranks for too long, they are developed quickly as professionals and they are allowed to prove their talent rather than merely defeat over-matched foes for years. This is a combination of "ignoring" the amateur scoring system that has plagued amateur boxing for so long, great training, great desire of the individual fighters to prove themselves and brave promoting. This isn't a golden age of Japanese boxing, but the start of a revolution which I feel will continue for a long time. (Pictures-Top is courtesy of Boxrec.com and is Tomoki Kameda, middle is from Ohashi Gym and features Naoya Ioue and bottom is from Kosei Tanaka courtesy of Boxingnews.jp) |

Thinking Out East

With this site being pretty successful so far we've decided to open up about our own views and start what could be considered effectively an editorial style opinion column dubbed "Thinking Out East" (T.O.E). Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed